If you work in a nonprofit, you have probably been asked some version of this question: “What difference are we actually making?” It sounds simple, but answering it well is one of the hardest parts of the job.

I have seen organizations doing meaningful work struggle to explain their impact beyond activity counts. They can tell you how many people attended a program, but not what changed because of it. That gap is exactly where outcome measurement matters.

This article is written for learning professionals and nonprofit leaders who want outcome measurement to support real decisions, not just reports. We will look at how nonprofits measure outcomes in practice, what usually goes wrong, and how to build systems that help teams learn and improve.

When outcomes are measured with intention, they sharpen strategy, strengthen programs, and make impact visible without turning measurement into a burden.

What Outcomes Mean in a Nonprofit Context

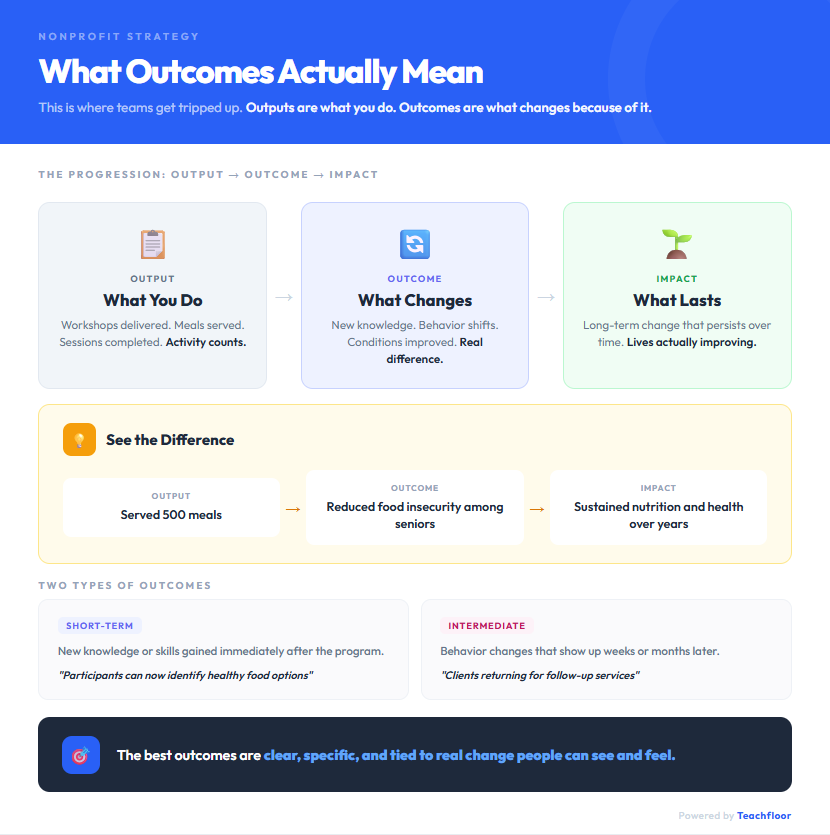

This is where many nonprofit teams get tripped up, even experienced ones. Outputs are what you do. Workshops delivered. Meals served. Sessions completed. Outcomes are what change because of that work.

For example, serving 500 meals is an output. Reduced food insecurity among seniors is an outcome. Long-term impact goes even further and asks whether that change lasts over time.

Counting activity feels productive, but it does not tell you if lives are actually improving. That is why how nonprofits measure outcomes matters so much.

Short-term outcomes might show new knowledge or skills. Intermediate outcomes reflect behavior changes, like clients returning for follow-up services. A common misconception is thinking outcomes must be complex. In reality, the best ones are clear, specific, and tied to real change people can see and feel.

Why Measuring Outcomes Matters for Learning and Decision-Making

When outcome measurement works, it changes how people think, not just what they report. The most effective nonprofits do not measure outcomes to satisfy funders. They do it to learn faster and make better decisions.

Outcomes act like feedback loops. They tell you whether a program is doing what you believe it is doing. I once worked with a workforce nonprofit that tracked job placements closely.

The outcome data showed placements were high, but six-month retention was low. That insight led them to redesign coaching and employer follow-up, which improved results without adding new programs.

This is how outcomes improve program quality. They reveal gaps between intention and reality. Instead of asking “Did we deliver the service,” teams start asking “Did the service help in the way we expected.”

Outcome data also sharpens strategy. Leaders can see which programs deserve more investment and which need adjustment. Over time, this builds organizational learning.

Staff become more comfortable testing ideas, reviewing results, and adapting. Measurement stops feeling like oversight and starts feeling like a shared tool for doing better work.

How Nonprofits Measure Outcomes in Practice

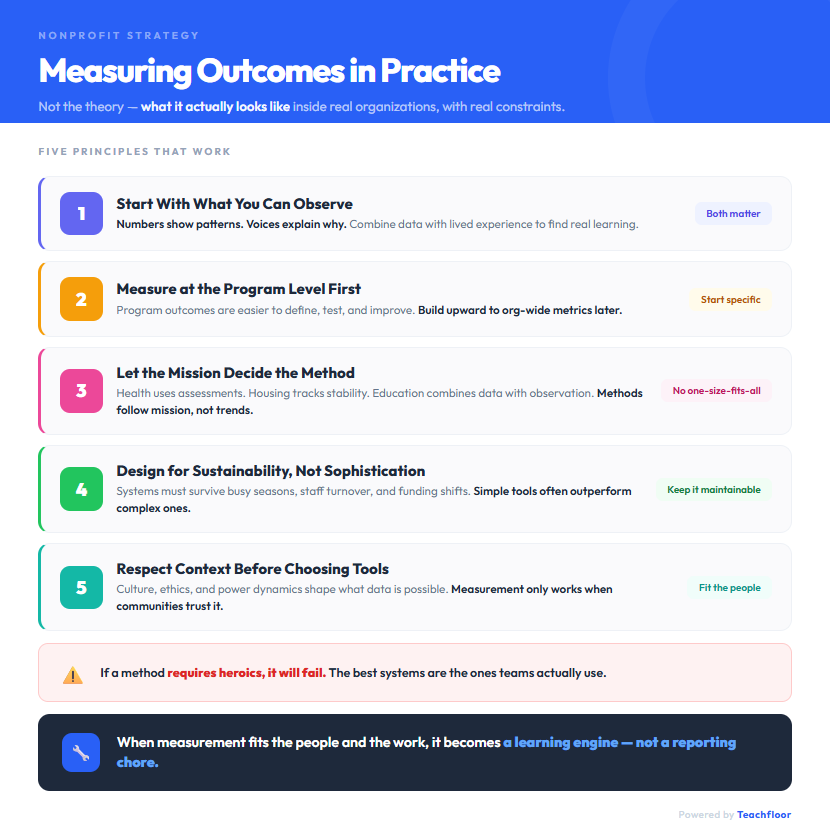

This is the part most people really want to understand. Not the theory, but what measuring outcomes actually looks like inside real nonprofit organizations, with real constraints.

Start with what you can observe without guessing

The strongest outcome systems begin with evidence you can see and hear. Numbers show patterns. Lived experience explains what those patterns mean. When one is missing, important gaps in perspective appear.

A youth mentoring nonprofit might track attendance and graduation rates, then follow up with short conversations about confidence or motivation. The numbers confirm change. The voices explain why it happened and what influenced it. That combination is where real learning starts.

Measure where change actually happens

Experienced nonprofits start at the program level, not the organizational level. Program outcomes focus on what shifts for participants inside a specific service. They are easier to define, easier to test, and easier to improve.

Organization-wide outcomes only work after program-level measurement is stable. Teams that try to measure everything at once usually create noise instead of insight. Those that build upward create clarity.

Let the mission decide the method

There is no universal way to measure outcomes. Health nonprofits rely on pre- and post-assessments. Housing organizations track stability months after placement. Education nonprofits combine performance data with observation and feedback.

Methods follow mission, not trends.

Design for sustainability, not sophistication

The best systems survive busy seasons, staff turnover, and funding shifts. I have seen small nonprofits collect strong outcome data with simple tools, while larger organizations abandoned complex systems no one could maintain.

If a method requires heroics, it will fail.

Respect context before choosing tools

Measurement works only when communities trust the process. Surveys work in some contexts. Interviews or group conversations work better in others. Culture, ethics, and power dynamics shape what data is possible.

When outcome measurement fits the people and the work, it becomes a learning engine instead of a reporting chore.

Writing Clear and Measurable Outcome Statements

This is where many nonprofits lose clarity. Weak outcome statements describe effort instead of change. “Deliver career workshops” is activity. An outcome explains what is different because the work happened.

A strong statement focuses on change you can observe. For example, “participants improve their ability to prepare a job application within three months” can actually be measured. Vague phrases like “increase awareness” or “strengthen skills” sound positive but offer no direction.

Defining who is changing matters just as much. “Clients improve job readiness” is unclear. “First-time job seekers demonstrate improved interview skills” gives focus and accountability.

Clear outcome statements describe change, name the population, and set a realistic time frame. When outcomes are specific, measurement becomes useful instead of confusing.

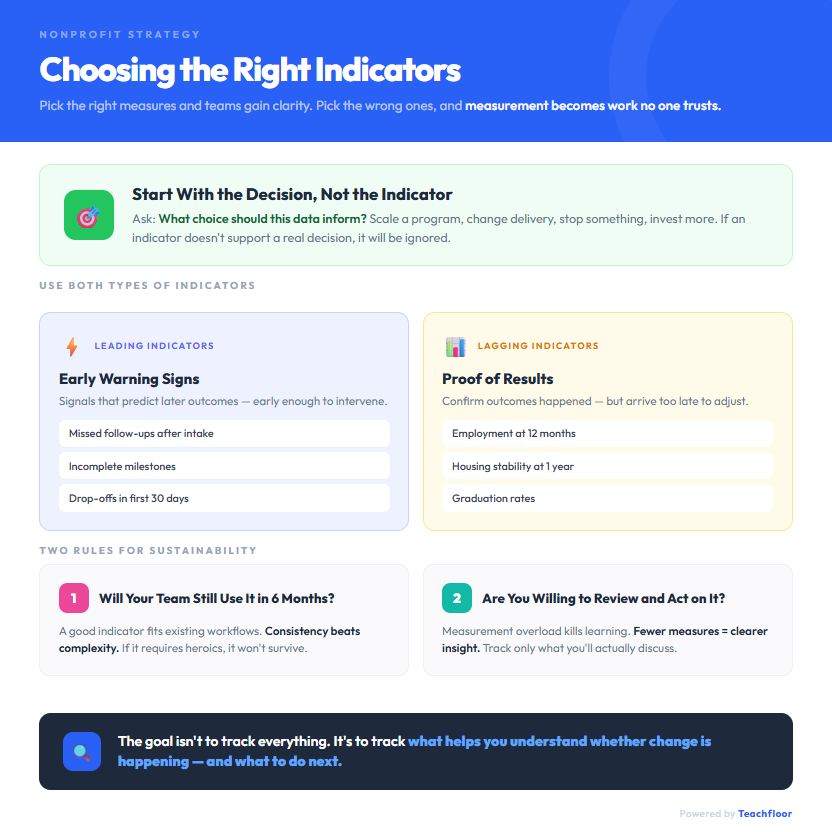

Choosing the Right Indicators and Measures

Choosing indicators is where outcome measurement becomes either practical or exhausting. Pick the right measures, and teams gain clarity. Pick the wrong ones, and measurement turns into extra work that no one trusts. The goal is not to track everything, but to track what actually helps you understand whether change is happening and what to do next.

Start with the decision you are trying to make

Top-performing nonprofits do not start with indicators. They start with decisions. Ask yourself what choice this data should inform. Scale a program, change delivery, stop something, or invest more. If an indicator does not clearly support a real decision, it will end up ignored.

For example, tracking workshop attendance rarely changes anything. Tracking whether participants apply the skills within thirty days often does.

Separate early warning signs from proof

Many teams rely too heavily on lagging indicators because they feel safer. Outcomes like employment at twelve months or housing stability at a year confirm results, but they arrive too late to adjust.

Leading indicators act as early signals. Missed follow-ups, drop-offs after intake, or incomplete milestones often predict later failure. The most effective systems use both so teams can intervene before outcomes slide.

Choose indicators your team will still use in six months

Rigor is meaningless if it cannot survive daily operations. I have seen carefully designed measurement systems abandoned once staffing shifts or funding tightens.

A good indicator fits existing workflows and can be collected without heroics. Consistency beats complexity every time.

Protect focus by measuring less

Measurement overload kills learning. When everything is tracked, nothing gets attention. Experienced organizations limit indicators to what they are willing to review, discuss, and act on. Fewer measures create clearer insight and stronger accountability.

Collecting Data Without Overburdening Programs

This is where outcome measurement usually breaks down. Not because people resist learning, but because data collection starts competing with service delivery. When that happens, both suffer.

The best approach is to weave data collection into the natural flow of the program. If staff already meet participants at intake, that is where baseline questions belong. If follow-ups are part of normal support, outcome checks can live there too. Data should feel like part of the work, not an extra task added at the end of the day.

Fatigue is real, for staff and participants. Long surveys, repeated questions, and unclear purpose drain goodwill fast. I have seen programs improve response rates simply by explaining why the data matters and how it will be used. Fewer questions, asked at the right time, usually produce better answers.

Moral responsibility is as important as getting things done efficiently. Participants should understand what they are sharing and feel safe doing so. Trust affects data quality more than tools ever will.

High-quality data comes from respectful, realistic systems that people can sustain.

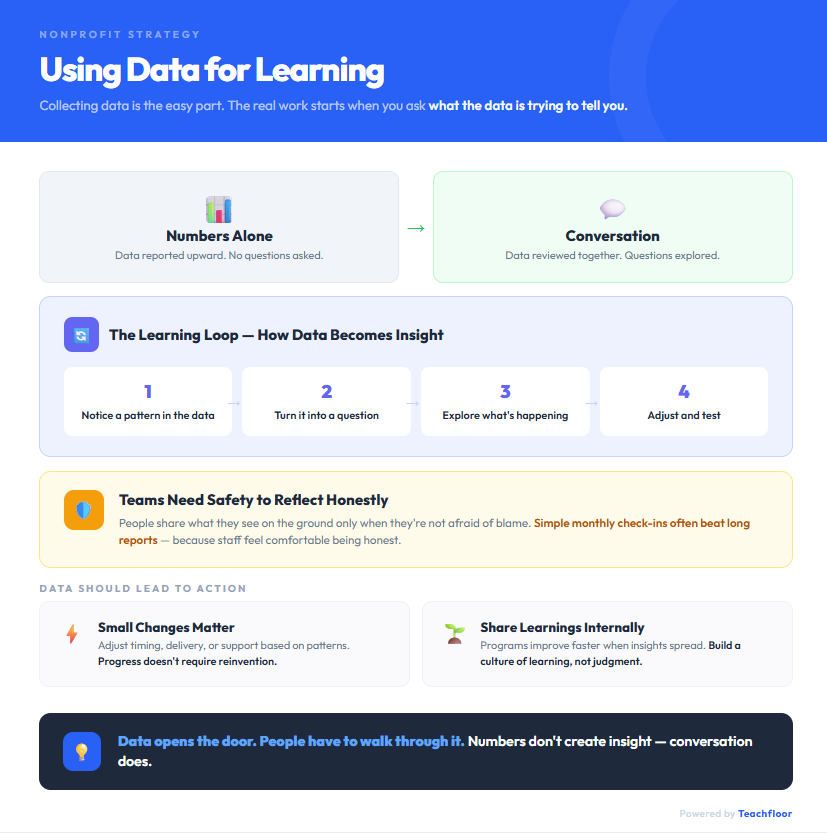

Using Outcomes Data for Learning and Improvement

Collecting outcomes data is the easy part. The real work starts when you sit down and ask what the data is trying to tell you. Numbers alone do not create insight. Conversation does.

Strong nonprofits turn data into learning by reviewing it together, not just reporting it upward. For example, a program team might notice that participant outcomes dip after the third session. That observation becomes a question. What is happening at that point in the program? Is the content too dense? Is attendance dropping? Data opens the door, but people have to walk through it.

People reflect more effectively when they feel secure and supported. Teams need space to talk honestly about what is not working without fear of blame. I have seen simple monthly check-ins replace long reports and lead to better adjustments because staff felt comfortable sharing what they were seeing on the ground.

Outcome data should lead to action. Small changes to timing, delivery, or support can make a real difference. Sharing what you learn internally helps programs improve faster and builds a culture where measurement supports learning, not judgment.

Reporting Outcomes to Funders and Stakeholders

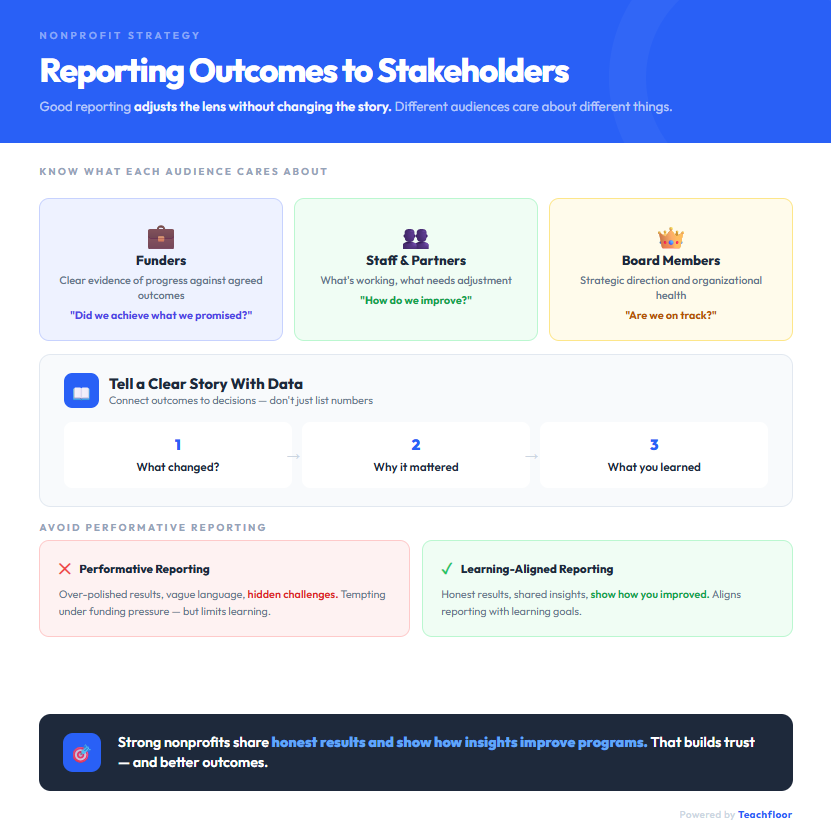

Outcome reporting works best when it respects the audience without losing the truth. Funders, board members, and partners care about different things, and good reporting adjusts the lens without changing the story.

For example, a foundation may want clear evidence of progress against agreed outcomes, while staff and community partners care more about what is working and what needs adjustment. The mistake is trying to satisfy everyone with the same report. That usually leads to vague language and over-polished results.

Telling a clear story with data means connecting outcomes to decisions. Instead of listing numbers, explain what changed, why it mattered, and what you learned. A housing nonprofit might report that placement rates stayed steady but follow-up support improved long-term stability. That shows progress and reflection.

Performative reporting is tempting, especially under funding pressure. It hides challenges and limits learning. Strong nonprofits align reporting with learning goals, sharing honest results and showing how insights are used to improve programs.

Common Mistakes Nonprofits Make When Measuring Outcomes

After years of working with outcome measurement across nonprofit organizations, the mistakes are surprisingly consistent. They rarely come from lack of effort. They come from good intentions applied in the wrong way.

Counting work and calling it impact

One of the most common mistakes is assuming activity equals change. A nonprofit reports that it served 300 clients or delivered 50 workshops and treats that as success. Those numbers only show effort. Without evidence that something changed for participants, they do not explain whether the program worked.

Either drowning in data or flying blind

Some organizations track everything they can measure and review almost none of it. Others track a single metric and expect it to tell the whole story. Both approaches fail. Experienced teams choose a small set of measures tied to real decisions they need to make.

Collecting data that never leaves a spreadsheet

I often see nonprofits invest time in surveys and reports that no one discusses afterward. When data is collected but never reviewed with staff, it becomes administrative work, not learning. Measurement only matters when people reflect on it and adjust their work.

Building systems only to satisfy funders

Designing outcome measurement solely for funder reports weakens its value. When data exists only for compliance, teams disengage. The strongest nonprofits design measurement to improve programs first and adapt it for external reporting second.

Conclusion

Measuring outcomes well is less about perfect data and more about disciplined learning. The nonprofits that get this right are not chasing metrics to impress funders.

They are asking better questions, paying attention to what changes for people, and adjusting their work based on what they see. Outcome measurement works when it becomes part of how teams reflect, learn, and make decisions, not a separate reporting task.

One practical piece that often supports this learning loop is having a clear way to train and align people across the organization.

Staff turnover, volunteer onboarding, and program changes all affect outcomes. When learning is inconsistent, measurement suffers. That is where an LMS fits naturally into a nonprofit’s outcome strategy, not as a tech add-on, but as infrastructure.

Many nonprofits choose Teachfloor because it supports how learning actually happens in mission-driven work.

Teams use it to onboard staff and volunteers, run cohort-based programs, facilitate discussions, collect reflections, and track progress over time. It works well for nonprofits because it connects learning, participation, and outcomes in one place.

When people learn together and apply that learning consistently, measuring outcomes becomes clearer, more meaningful, and far easier to sustain.

%201.svg)

.png)

.avif)

%201.png)

%201.svg)